Torn between the isolationist members of his own party and the Teddy Roosevelt-led faction howling for blood after the sinking of the Lusitania, Woodrow Wilson crafted a compromise: He would keep the U.S. out of the Great War — but only if people stayed out of his candy jar.

Wilson, who entered the Presidency with a reputation for aloofness, assiduously cultivated it further once in office. He paid a White House gardener $10 to leave baseballs, model planes, and hoops around the White House lawn, maintaining the air of the scary old neighbor. Tellingly, he later took the $10 out of the gardener's pay, claiming to smell whiskey on his breath.

But while staffers feared Wilson, they loved his candy jar. The jar on Wilson's desk, stocked with fresh Clark Bars everyday, had become a frequent stop for White House aides, Cabinet members, and on several occasions, Vice President Thomas Marshall. Stepping out of his office one day for five minutes, he came back to find his jar bare. Outraged, Wilson called an emergency joint session of Congress to outline his plan.

The plan was not as well-developed as it would come to be remembered in later years. Of the 14 points, 12 were a variation of "Stay the hell away from my candy jar." But the key phrase took on a life of its own:

"Be it hereby resolved:

That Congress shall declare no act of war against a sovereign nation, regardless of any belligerence toward our nation or its allies, until a confection of or belonging to the President, among an assemblage of such sweets found in his designated jar, shall be found to be removed from said location without the authorization of the President or the First Lady."

First Lady Edith Bolling Galt Wilson privately worried the curmudgeonly request would make America turn against the Presidency. Early polls were inconclusive; then, Wilson's PR department sprang to work. They blanketed newspapers with full-page drawings of Woodrow Wilson slapping Red Sox center fielder Tris Speaker's hand away from the jar and cheekily admonishing Speaker, "Now, now, Tris. The Red Sox can't win everything." The Irving Berlin-penned song "Keep Your Hands Off The President's Candy (Keep Your Hands Off My Ragtime Gal)" sold 5 million copies of sheet music, making it 1916's biggest seller. (Rumor had it that Berlin knocked the song out in real time, aided by the gun pointed at his temple by chief propagandist George Creel.)

Wilson rode the ensuing popularity to a come-from-behind win in the 1916 elections. But the fragile candy détente was too good to last. After agents intercepted a note from a German diplomat seeking to enlist Mexico in the war, Wilson began looking for ways to break his popular pledge. He moved the fabled jar first out into the hallway, then by the front entrance, and finally, right outside the gates of the White House. Trained all too well, the public refused to bite. Then 4-year-old Johnny Thompson of Bend, Oregon, overcome by his first sight of a Moon Pie, ran to the jar and swiped a piece. The action gave rise to the phrase "Johnny-on-the-spot."

Wilson, talking with a White House photographer and a cluster of aides, jerked his head toward the window.

"Get Congress," he said. "Now."

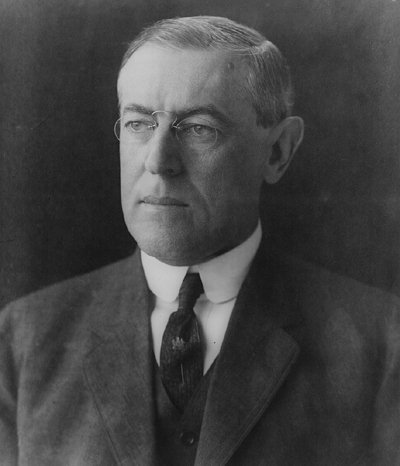

(OK, that's not really reimagining him. But I think Woodrow Wilson is unique among all the presidents; even if you've never cracked a U.S. History textbook in your life, you've got him figured out.)